CEOs share approaches to bearing ultimate responsibility

CEOs share approaches to bearing ultimate responsibility

- January 20, 2017 |

-

CEO Update

CEO Update

Identifying problems early, admitting errors, listening to your team but trusting your gut, and putting your ego aside are critical

Jan. 20, 2017

By William Ehart

By William Ehart

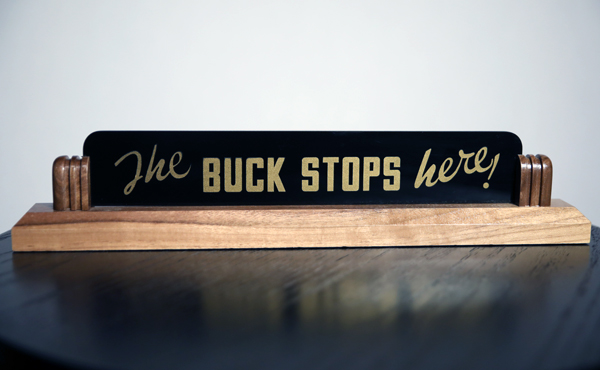

Since the buck always stops with the CEO, how do successful association executives recognize when mistakes are rippling through their organizations?

And what are the common attributes of good management that prevent major failures?

CEO Update interviewed seven veteran association leaders and some universal themes emerged: Empower and listen to your team, but closely monitor progress. Check your ego and don't take things personally—but know when to listen to your gut. Be self-aware and comfortable in your own skin. Learn from the inevitable mistakes, own them, but don't repeat them.

Failures can manifest in small ways at first, with the fault hard to pinpoint. But you must be able to recognize and respond to those signs—and quickly address problems.

A bad senior staff hire may drive some of your best employees away. Failing to watch the progress of an initiative—and adjusting resources and expectations along the way—can result in much higher costs and unwelcome surprise for your board. And when staffers are reluctant to bear bad news, problems will fester.

Make sure your team is willing to give you the straight dope.

Doug Culkin, who just retired after 17 years as CEO of the $28 million-revenue National Apartment Association, once hired a top staffer who proved disruptive to the organization. Despite Culkin's open-door policy and frequent interaction with employees, some staff were reluctant to tell him.

Fortunately, his general counsel heard the complaints, passed them on and Culkin took quick action.

"As soon as it becomes apparent that it's bad, you've got to go in and correct it, which in most cases means termination of the individual.

"Those are the places where we have to earn our salary. Nobody enjoys terminating people, but if you don't and you harm the organization—or worse, other people leave because you have not addressed the situation—then you've done further damage to the organization that you can't recover from.

"Typically, it's the good people who leave, so you have failed not only yourself and the organization, but you've failed the person who left," Culkin said.

‘Folks are going to notice that sometimes things run amok.'

Peter O'Neil, new CEO of the $32 million-revenue ASIS International, has learned the hard way to listen to his gut when hiring because staff input on personnel moves has not always proved reliable.

Peter O'Neil, new CEO of the $32 million-revenue ASIS International, has learned the hard way to listen to his gut when hiring because staff input on personnel moves has not always proved reliable.

But having hired the right people, O'Neil also has erred in failing to listen to them. One mistake cost his previous association—the $16 million-revenue American Industrial Hygiene Association, which he ran for 16 years—nearly $200,000.

"I've always tried to feel no shame and actually take pride in the fact that sometimes you make a mistake and it's OK to admit that," O'Neil said. "The greater sin is to make a mistake that people are pointing out to you and to refuse to do anything about it."

"Folks are going to notice that sometimes things run amok and it's important to have the ability to hear that and put your own ego aside, especially if it's a project you dreamed up."

O'Neil conceived such a project about 10 years ago at AIHA.

"We invested about a quarter million dollars in an online library project that just completely went bust," he said.

"It was a service before its time and our pricing model just didn't work. I had some feedback to that point from various people, but I just so believed that we were doing the right thing that I didn't see some of the warning signs," O'Neil said.

Fortunately, about $80,000 spent on research proved useful in other areas, he said.

Learn the strengths of individual team members, and don't take things personally.

Heidi Brock, CEO of the $5 million-revenue Aluminum Association, said that when confronted with challenges she has benefited from management assessment tools that identify the strengths of individual team members and from engaging her team rather than taking challenges from association members personally.

Heidi Brock, CEO of the $5 million-revenue Aluminum Association, said that when confronted with challenges she has benefited from management assessment tools that identify the strengths of individual team members and from engaging her team rather than taking challenges from association members personally.

"We recently had a member re-evaluating the value proposition (of belonging to the association) and wondering whether it was getting a return on investment," she said.

"My tendency is to feel like I need to take this on myself or make it almost a personal issue, and fortunately I stepped back and engaged my chairman and engaged my team.

"We've been able to collaboratively troubleshoot the challenges and opportunities and identify certain members of our team to help pull together a response and the information we needed to put our best foot forward," Brock said.

A project management team can quickly spot red flags in new programs.

Shal Jacobovitz, CEO of the $124 million-revenue American College of Cardiology, closely tracks the progress of major initiatives with the help of ACC's project management office. Establishing timelines and metrics and quarterly updates keeps staff and board expectations in line when efforts bog down—as did the launch of the association's new website about a year ago. The site's new look and functionality were delivered three months behind schedule.

Shal Jacobovitz, CEO of the $124 million-revenue American College of Cardiology, closely tracks the progress of major initiatives with the help of ACC's project management office. Establishing timelines and metrics and quarterly updates keeps staff and board expectations in line when efforts bog down—as did the launch of the association's new website about a year ago. The site's new look and functionality were delivered three months behind schedule.

In the early stages, those responsible for a project may resent the involvement of an outside project manager, but such procedures are critical. In the case of the website, one of the problems identified was an insufficient number of programmers, Jacobovitz said.

"The initial impulse of people who submit their projects to our project management group is that they somehow are being micromanaged, but the opposite is true.

"It's about what are the red flags, and how can we as a management team help you?" he said. "It's not pointing fingers, it's more to say we need to do ‘X,' we need to marshal resources from other parts of the organization. Let's put other projects on hold because this is a higher priority."

‘Feedback from the people around me gives me a reality check.'

Dale Stinton, who is retiring this year as CEO of the $220 million-revenue National Association of Realtors, said a team approach helps prevent big foul-ups—and alerts him when he has fallen prey to his "biggest weakness": Hanging on to problem employees too long.

Dale Stinton, who is retiring this year as CEO of the $220 million-revenue National Association of Realtors, said a team approach helps prevent big foul-ups—and alerts him when he has fallen prey to his "biggest weakness": Hanging on to problem employees too long.

"We have a lot of very vocal members and a lot of volunteer involvement, so we are getting feedback on a daily basis," he said. "There are so many checks and balances in the system, and I by no means want this to sound arrogant, but I'm not often confronted with being wrong, at least as it relates to member activity.

"I'm far more introspective about staff, because when you're dealing with people, you can't always get it right.

"My weakness is I give (problem staff) too much time. I wait too long to realize I've made the mistake.

"I've asked myself why. It's because when we get to the CEO level, we think we're pretty good at evaluating people and training and mentoring. I have on a few occasions carried somebody longer than I should have because I thought I could save them.

"Feedback from other people around me, usually the HR folks, gives me a reality check," Stinton said.

‘You can't do everything.'

Like Stinton, Mary Logan, recently retired CEO of the $15 million-revenue Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation, knows she tends hang on to bad hires too long. "That's where I've made my biggest mistakes," she said.

Like Stinton, Mary Logan, recently retired CEO of the $15 million-revenue Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation, knows she tends hang on to bad hires too long. "That's where I've made my biggest mistakes," she said.

Logan tried to avoid forming her own strong opinions so she could better listen to staff input. But there was a time when she ignored blunt staff feedback on a project she was keen on. The result was not a disaster, but a learning experience.

"One of the things I was certain of was co-convening an event with another organization, and one person on my staff said this is going to take way longer than you think, it's going to involve a lot more people on staff doing stuff that they don't have time for and it doesn't fit in with your top priorities," Logan said.

The event was a nuclear power and health care workshop put on with the Idaho National Laboratory in 2012.

"It involved learning from another industry, it was awesome and really fun, and the people who attended it loved it," she said.

"But you can't do everything. It did not advance our organization, it did not support our top priorities, and one person on our team strongly believed that and I ignored him," she said.

Own your mistakes—don't point to others or to external factors.

Cam Fine, 14-year CEO of the $39 million-revenue Independent Community Bankers of America, said making mistakes is not the issue.

Cam Fine, 14-year CEO of the $39 million-revenue Independent Community Bankers of America, said making mistakes is not the issue.

"It's how you handle those mistakes that separates good CEOs from poor CEOs," he said. "To recognize their own mistakes, CEOs must first be self-aware. They must be comfortable in their own skin. They must understand their own strengths and weaknesses and they absolutely must check their ego at the door."

About four years ago, ICBA launched a major educational initiative in California, where its existing programs hadn't caught on.

"We put some major money behind it, probably half a million dollars, and it totally fell flat," Fine said. Competition in the market is fierce, and the banking culture in the state differs markedly from that in other states.

"That was a case of not doing good enough groundwork and listening and doing enough focus groups," he said. After a complete revamp, the project is now modestly successful.

"If you make a mistake, you have to own it. You cannot cast doubt on any other person or thing or external factor," he said.

MORE POSTS IN THIS CATEGORY: